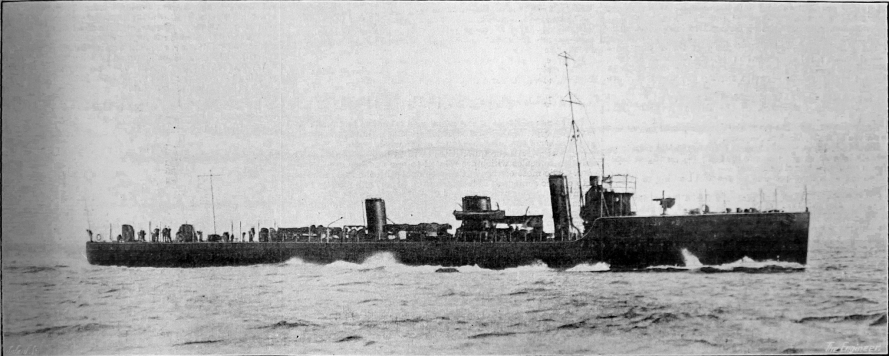

H.M.S. Shark

The Naval Programme of 1911–1912 included twenty ocean-going torpedo-boat destroyers of what is known as the Acasta class. Of these the first to run her trials at sea is the Shark, of which, by the courtesy of Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson, Limited, who built her, we are enabled to give the accompanying illustration. This firm is building two other boats of the same class, the Sparrowhawk and the Spitfire, the former of which was launched in October last. The other vessels of the class are being built by John Brown and Co., Limited, three, the Acasta, Achates, and Ambuscade; Messrs. Denny, one, the Ardent; Hawthorn Leslie and Co., Limited, three, the Christopher, Cockatrice, and Contest; the Fairfield Company, one, the Fortune; The Parsons company, one, the Garland; the London and Glasgow Company, three, the Lynx, the Midge, and the Owl; and Messrs. Thorneycroft, five, the Hardy, the Paragon, the Porpoise, the Unity, and Victor. The first of these, the Hardy, is being fitted with Diesel engines for cruising purposes.

All the vessels of the class are to be of approximately the same displacement, namely, 935 tons, and to have the same or approximately the same horse-power, namely, 24,500, the trial speed varying from 31 to 32 knots.

The dimensions vary slightly, the length from 257ft. to 260ft.; the beam from 26½ft. to 27ft.; and the draught from 8ft. to 8.3ft. The armament is the same in every case, namely, three 4in. guns and two torpedo tubes, and each vessel will carry a complement of 100 men. It is understood all of them will have water-tube boilers, and all be fitted for burning oil fuel.

The Shark herself is, like her sister vessels the Sparrowhawk and Spitfire, 260ft. long by 26ft. beam, and has a draught of 8.3 ft. She is propelled by three screws, as are to be the Acasta, Achates, Ambuscade, Christopher, Cockatrice, Contest, Lynx, Midge, and Owl, while the Ardent, Fortune, Garland, Paragon, Porpoise, Unity, and Victor are only to have two propellors.

We understand that the Sparrowhawk and Spitfire are in a forward state of construction, and that their builders have two other similar torpedo-boat destroyers in hand, namely, H.M.SS. Sarpedon and Ulysses.

A bridge, the longest cantilever in the world, finally crossed the St Lawrence in August 1917, The photo is from

A bridge, the longest cantilever in the world, finally crossed the St Lawrence in August 1917, The photo is from